Go Back

Go BackShare

Reliable Assessment for Bottom-up Accountability in Andhra Pradesh

By Devika Kapadia

Jul 28, 2019

Most public education systems function through the “long route of accountability,” where teachers and education officials are not directly accountable to parents, who have limited “client power.” Private school markets, however, function through a much shorter route of accountability, with parents voting with their feet for their preferred services and private providers orienting to that demand.

Most public education systems function through the “long route of accountability,” where teachers and education officials are not directly accountable to parents, who have limited “client power.” Private school markets, however, function through a much shorter route of accountability, with parents voting with their feet for their preferred services and private providers orienting to that demand. The desire for responsiveness to their demands from their children’s schools (whether to do with teacher attendance or English medium) might partly explain an ongoing migration of students from government schools to low-fee private schools. Yet, despite the fact that private schools ought to be more accountable, this doesn’t reflect clearly in the outcome – student scores in private schools are only slightly improved over their public counterparts after taking into account student socio-economic background.

This suggests that parents aren’t always able to get what they are paying for. According to a recent study by the Azim Premji Foundation, the primary factor influencing demand for private schools is improvement in their children’s learning (rather than better discipline, access to more affluent networks, prestige, etc.). But most parents don’t have a tangible way to measure these improvements – or learning outcomes at all. 83% of schools nationwide do not extend up to class 10, and so a majority of parents do not have reliable, external data on school learning outcomes like average board exam scores or pass percentages. In the absence of information about the quality of their children’s schools and other options in the market, they must rely on (potentially weak) proxies as markers of quality, like a computer lab or mandated uniforms. This asymmetry means that they are neither informed consumers on actual learning when they make their school choice, nor can they effectively advocate for or track improvements in learning at the schools their children attend.

From the perspective of supply, the absence of reliable learning outcomes data distributed to parents means that school owners have no channel to credibly communicate improvements in learning, and hence, little incentive to invest in it. It should, therefore, fall to the government – as a stakeholder invested in both improving schools and empowering parents – to provide public, comparative, school-wise learning outcomes information.

There is global and Indian research evidence on the impact that active and public distribution of reliable school rating information has on learning outcomes and fee levels, particularly in private schools. In villages across 3 districts in Punjab, Pakistan, Andrabi et al. measured the impact of comparative learning outcomes information in enclosed schooling markets, that is, villages with a range of choice, government or private, for parents to choose from. When average scores of all schools in the village were distributed to parents, researchers found the market aligned to produce a statistically significant improvement in scores that sustained over 8 years.

In rural Ajmer, Rajasthan, researchers provided different forms of information to different stakeholders in isolated treatments, with parents receiving information on how their child performed with respect to the class in one; schools receiving information on the distribution of their own students’ performance in another; schools receiving information both on their own students’ performance and those of other schools in a third; and schools and parents receiving information on inter-school and comparative reports on different schools in a fourth. On evaluation, it emerged that only when comparative information is provided to parents and schools do scores in private schools improve significantly. One implication of this is that the information that most regularly goes home to parents – student reports – is not very useful in improving scores. Another is that supply-side competition – where schools see how they compare to their competitors and are motivated to improve – does not take place until this information is available to parents.

Yet nationally, comparative school-wise learning data is not publicly available. The government does publicly provide school-wise information, but not on school quality. U-DISE (Unified District Information on School Education) school report cards were designed partly for bottom-up accountability, but are instead largely used for administrative and fund allocation purposes. These reports capture information on enrolment, medium of instruction, school infrastructure, etc., collected through a self-reporting system, where schools fill out hard copy formats which are then digitized.

The do-it-yourself approach used for DISE is the least resource intensive for an exercise of such immense scale, but it doesn’t work for assessment metrics. Given the combination of parental emphasis on test scores and the difficulties involved in auditing learning scores, assessments administered and data reported by teachers and schools are at great risk of inflation. Manipulated assessment data is of little value to parents as they compare schools – it will only distort their existing heuristics for quality.

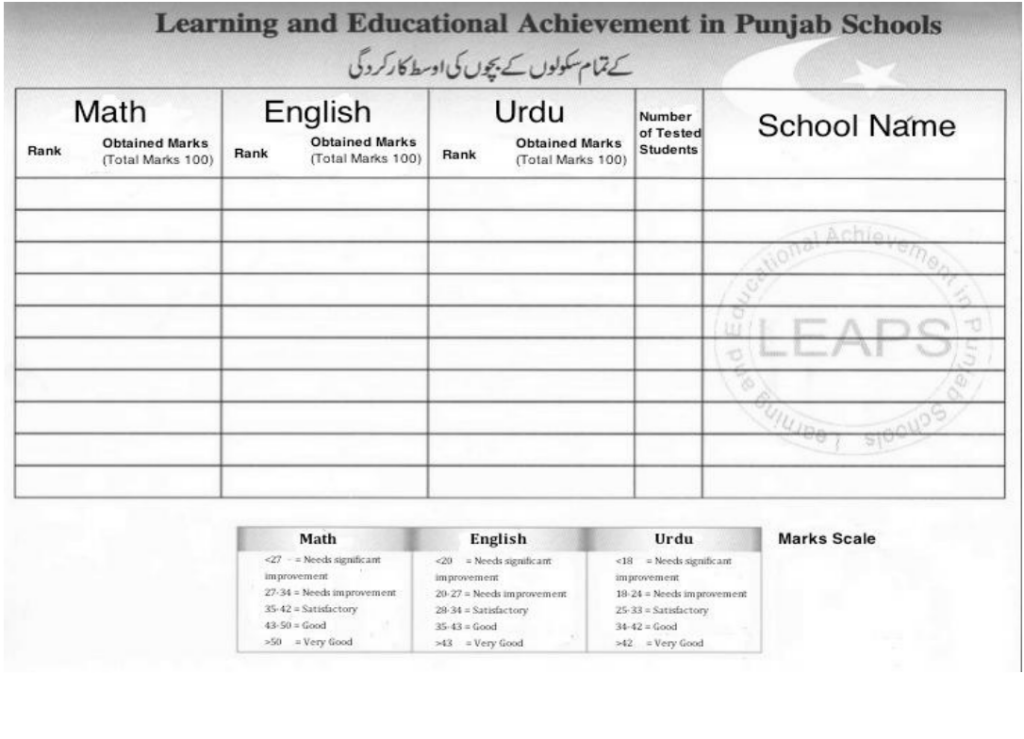

Reliable government-led key stage census assessments with results disseminated widely are, therefore, critical for private school accountability. Given this, in an attempt to improve data reliability in order to eventually disseminate comparative school-wise results, CSF’s Private Schools team supported the Andhra Pradesh Commissionerate for School Education in piloting a large-scale digital assessment of all class 4 students in every school in the AP database (which includes only recognized private schools) in the district of Prakasam.

In Andhra Pradesh’s case, resources were not a bottleneck to implementing a large-scale digital assessment. Both the hardware for a district (3,500 tablets) and the manpower (370 Cluster Resource People invigilators) were readily available to the department of education. Similarly, we found technical solutions already existed in the private sector for standardized assessment creation (selection and “anchoring” of questions across sets through application of Item Response Theory, a statistical technique to standardize assessment difficulty and ensure reliability) as well as app development (offline, with randomization capacities and an in-built timer for each section).

The challenge was to pull these pieces together into a coherent and contextual exercise – adapted for children who might not be digitally literate, involving daily travel across a rural district, led and implemented by district education staff with various other responsibilities. In February 2019, 27,370 students were assessed using tablets across 1,694 schools in Prakasam, Andhra Pradesh.

Digital assessment done through tablets reduces the possibility of cheating in a few key ways: through randomization of assessment questions into different sets from a large, linked question bank such that various different versions of an exam are taken in a single classroom, making it difficult for an invigilator to dictate answers; monitoring of geolocation and timestamps to ensure that exams happen when and where scheduled; and the impossibility of post-facto tampering since tests are submitted directly.

The use of tablets also streamlines the cumbersome data entry, ID linking and compilation that a paper-based assessment with a self-reporting system would require. These measures are by no means exhaustive (and the cynical perspective dictates that people will always come up with new ways to circumvent new barriers) – but we thought it worthwhile to make this sort of manipulation a little more difficult, and the data a little more reliable.

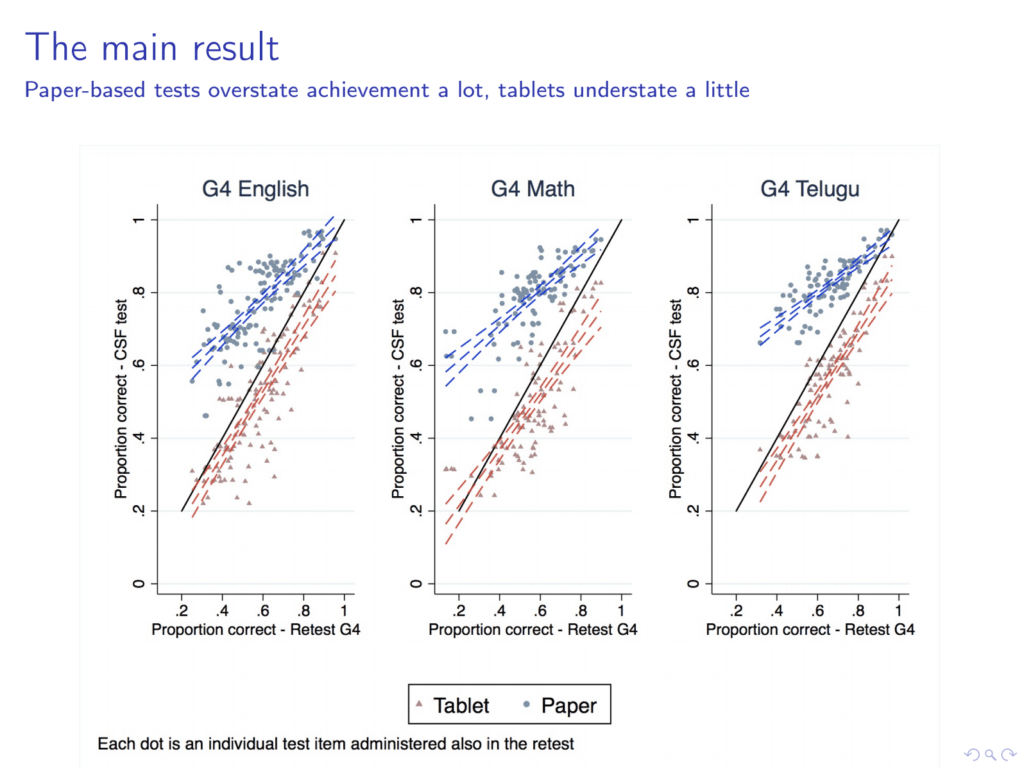

Professor Abhijeet Singh, who evaluated the project, found that data from tablet-based assessments is more reliable than data collected from pen-and-paper assessments. (He discusses his findings here.)

Another evaluation of this project will measure the impact that the public provision of this data, through report cards, has on school choice, accountability and eventually learning outcomes. In the interim, however, three things emerge quite clearly – first, the implementation of census digital assessment at scale through the government is possible, and it is relatively inexpensive if the state already possesses the hardware. Second, collecting census data repeatedly in a way that maintains its reliability would provide a base for a plethora of reform efforts across the private and public school systems – from support targeting and accountability in the public system, to in-built evaluations of policy measures, to outcome-based regulation for private schools. And third, given the sacrifices that parents make to give their children access to education, the reliable, school-specific quality indicators which this process produces is information parents are owed.

Keywords

Authored by

Devika Kapadia

Program Manager, CSF

Share this on