Go Back

Go BackShare

Increasing Learning Time in Preschools in India

By Aditi Nangia, Ashna Shah and Krishnan S

Aug 25, 2022

Quality early childhood education for children between the ages of 3 to 6 is a crucial step to getting them ready for school and life. Apart from the obvious inputs to strengthen ECE such as curriculum, training and monitoring, etc., the biggest constraint to solve is low learning time. This article reflects on the gaps in ECE provisioning in Anganwadis and government schools and suggests ways to increase learning time.

By now, it is widely acknowledged in policy and academic circles in India that quality early childhood education (ECE) for children between the ages of 3 to 6 is a crucial step to getting them ready for school and life. India’s pertinent policies (the National ECCE Policy 2013 and National Education Policy 2020) are progressive and far-reaching in their vision. Yet, absolute levels of learning in pre-school years remain alarmingly low. In the absence of government data on school readiness, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) Early Years report (2019) and the India Early Childhood Education Impact (IECEI) Study offer us insights. These studies highlight that approximately only a third of 5-year-olds were able to count objects in a pre-numeracy task and only 1 in 4 were able to complete a listening comprehension task in the local language.[1][2]

There are many reasons that one could attribute these poor outcomes to. The curriculum across many states is not very well-structured. Even if it is, pre-school teachers/Aanganwadi teachers are not adequately trained on developmentally appropriate ECE pedagogy. The concept of ongoing teacher support and mentoring is almost absent in this space. Parents are often not treated as equals in their child’s learning journey, and consequently are not given the knowledge and tools to support their child at home. Evidently, all of these issues need to be addressed across both the Anganwadi and the school network in India.

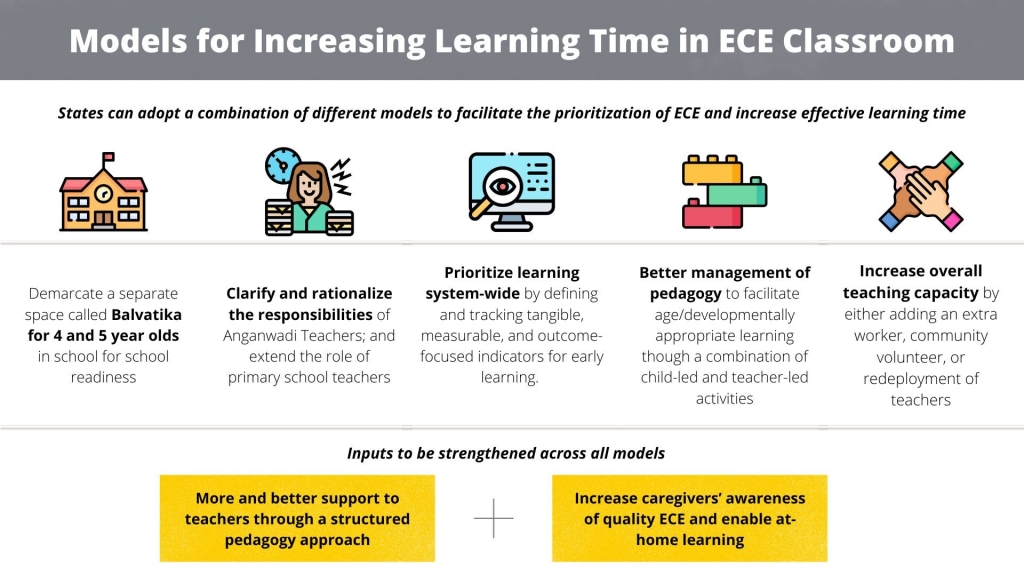

However, even if all of these inputs were to be strengthened, there is arguably one more structural constraint that needs to be eased systemically- adequate learning time across all our pre-schools. Between the myriad of registers that need filling in an Anganwadi and the multi-grade nature of primary school classrooms, most children attending government-provisioned ECE centers do not get the requisite time or the right environment to learn. In the below section, we lay out some suggestions and models to increase effective learning time for our youngest learners.

A. Demarcate a separate space called Balvatika for 4 and 5 year olds in school;

B. Clarify and rationalize roles and responsibilities;

C. Prioritize learning system-wide;

D. Better management of pedagogy;

E. Add or re-deploy teaching capacity;

A. Demarcate a separate space called Balvatika for 4 and 5 year olds in school

46 lakh 4 and 5-year-olds across India enter government schools directly in Class 1, unprepared to face the rigors of formal schooling.[3] In 21 Indian States, the entry age for grade 1 is 5 years (as opposed to 6) and only 19% of government schools have pre-primary sections. At the same time, most 5 to 6-year-olds are not in Anganwadis. Only ~27% children in the 5 to 6 age cohort are in Anganwadis, as compared to 50% of 4-year-olds.[4]

The 4 and 5-year-olds enrolled in government primary schools can be demarcated as part of a dedicated Balvatika/Zero grade to ensure that they are getting age-appropriate engagement and literacy/numeracy support required before they enter grade 1 at age 6. This can be implemented in a phased model, beginning with schools with large enrollment, where dedicated infrastructure and teachers are already available. Creating this dedicated Balvatika space will shift the discourse around early learning and could lead to multiple other cascade effects including more involved parents and greater share of enrolment in government schools in Grade 1.

B. Clarify and rationalize roles and responsibilities

The streamlining of roles and responsibilities for teachers in classrooms across Anganwadis, Balvatikas, and Government Primary schools can enable creation of dedicated time for ECE.

Role clarity and prioritization for Anganwadi teachers, helpers, Asha workers, and Midwives: A network of 13.8 lakh Anganwadis, run by over-burdened Anganwadi teachers with the support of a helper, are in charge of delivering the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) covering health, nutrition, and education for over 3 crore children aged 0-6. Education is only 1 among 21 responsibilities of an Anganwadi Teacher (AWT) and studies suggest that only 38 mins/day are spent on education, insufficient for meaningful ECE.[5] Anecdotal data from observational studies in Telangana and Uttar Pradesh show that AWT spend most time on data entry and paperwork, deprioritizing pre-school education when such tasks are at a high intensity.

Minimizing duplication and overlap in roles and responsibilities of an Anganwadi worker/teacher, helper, Asha, and midwife in health and nutrition activities can help make time for pre-school education. Within a centre, the role of an Anganwadi helper may be expanded to either include some of the teachers’ responsibilities or formally engage with younger children in pre-school activities to free up the teacher’s time for engaging with older children (5 to 6-year-olds) to make them school ready. Telangana and Maharashtra are two states which are actively considering some of these structural reforms in their Anganwadis.

Extend the role of primary school teachers to support co-located Anganwadis: Nearly 5 lakh out of 8.9 lakh government primary schools have a co-located Anganwadi. This means that the Anganwadi is housed within the premises of the primary school, offering hitherto unleveraged scope for learning synergies. The AWT can be paired with a primary teacher from the same school to co-develop ECE teaching-learning materials and receive implementation support through observation and mentoring. Both the teachers could attend professional development on ECE and jointly be held responsible for ECE delivery. Areas where the primary teacher could support the AWT could include prioritization of daily and weekly schedules, multi-grade teaching approach, and classroom management. UP has already been ensuring that the primary teachers include the older Anganwadi kids in the 3-month Vidya Pravesh module till September this year. A similar model may be implemented for the entire year, wherein the grade 1 teacher focuses on school-readiness for the older children enrolled in the co-located anganwadis for at least 2 hours everyday.

C. Prioritize learning system-wide

Another structural change that needs to be introduced is a district-level prioritization of learning for 3 to 6-year-olds by all stakeholders. All review meetings by both the ICDS and the education department leadership need to clearly emphasize effective learning as a key metric to track for our ECE cohorts, wherever they may be. Classroom observation formats by supervisors, Child Development Project Officers (CDPO), block and cluster resource persons, etc., need to specifically include learning metrics around the type of learning activities conducted, effectiveness of such activities, and time dedicated to them on a daily basis.

Similarly, at a National level, in the Ministry of Finance’s outcome framework for Budget 2022-23, the expected outcome for this years’ budget allocation to Mission Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 is only focused on improvement of nutritional and health status of children in the age group of 6 months to 6 years.[6] While these are undoubtedly important, the outcomes also need to include pre-school education. Both departments (Education and WCD) need to work together at a district level to define and track tangible, measurable, and outcome-focused indicators for early learning.

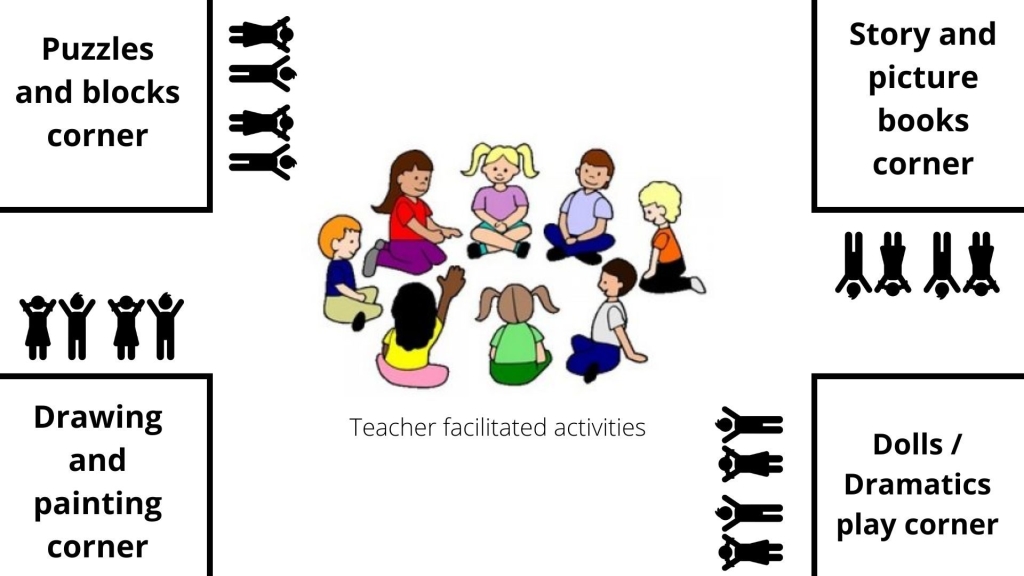

D. Better management of pedagogy

Both our Anganwadis and our primary school classrooms are multi-grade in nature. This means that any given classroom has at least two (typically more) age cohorts of children sitting and learning together. However, in the early years, this can be leveraged as a significant advantage, given that the recommended pedagogy for ECE is play-based and child-initiated. Anganwadi and pre-school teachers could be trained to set up child-led learning centres in the classroom while attending to a subset of children with direct instruction at the same time. This learning pedagogy has been implemented by many non-profit programs across geographies. If set up and practiced well, it is an elegant and age-appropriate way to increase effective learning time for all children in a classroom. The below picture is an example of setting up learning stations, adapted from the National ECCE curriculum framework document.

E. Add or re-deploy teaching capacity

The obvious yet expensive way of increasing effective learning time would be to add dedicated teaching capacity in ourAanganwadis and pre-schools.

Additional half time Anganwadi teacher: An experimental study conducted by J-PAL in Tamil Nadu aimed to solve for the Anganwadi workers’ time constraints by adding an extra half-time community teacher to conduct pre-school activities. The study demonstrated a high return of investment in terms of early childhood development, with an additional AWT, and adding a half-time teacher in AWCs, doubling net pre-school instructional time. The study estimates the value of future earning gains resulting from the program’s educational impacts to be 11-12 times the cost.[7]

Across all our Anganwadis, this additional (half-time) teacher can be hired with a budget of INR 6455 Crores.[8] To reduce this further, various models can be explored where the additional teacher is allocated either per Anganwadi, or shared between 3 to 4 close Anganwadi centers, or hired by the community, based on a set of guidelines and subsequently trained for ECE instruction by the WCD.

Community workers or volunteers in pre-schools: Some states including Punjab and Karnataka have managed to mobilize cadres of community volunteers to teach pre-school classes. The volunteers (sometimes appointed by the village panchayat) enable primary schools to add and run a Balvatika section with a dedicated teacher thereby ensuring effective learning time.

Inter-district re-deployment of teachers to zero class/Balvatika, starting with large schools: Currently, only 56k government pre-primary sections have a dedicated teacher as per U-DISE. If the Grade 1 entry age is raised to 6 years across all provision channels, 46 lakh 4 and 5-year-olds enrolled in government schools can be moved to a zero class/Balvatika, freeing up 1.53 lakh primary teachers across India. A state level analysis of 4 and 5-year-olds in the government school system with the associated teachers, and a closer look at school enrolment trends to identify large schools will help States identify schools where well-equipped Balvatikas can be started.

View Article References

Keywords

Authored by

Aditi Nangia

Senior Project Lead, CSF

Ashna Shah

Project Manager, CSF

Krishnan S

Senior Program Manager, CSF

Share this on