Go Back

Go BackShare

Findings from CSF’s Research on Early Childhood Education in India

By Aditi Nangia, Ashna Shah and CSF Editorial Team

Jan 10, 2024

India has nearly 80 million children in the age group of 3-6 years. Decades of multi-disciplinary research have firmly established the long-term positive effects of investing in high-quality ECE programmes for children, their families and society as a whole. CSF undertook a situational analysis of ECE provisioning to understand the challenges and opportunities that can provide options to enhance ECE for young learners, this article covers insights from the classroom observations and interviews conducted as part of the study.

India has nearly 80 million children in the age group of 3-6 years. Decades of multi-disciplinary research have firmly established the long-term positive effects of investing in high-quality ECE programmes for children, their families and society as a whole. The 2013 National ECCE Policy (MWCD) and National Education Policy 2020 (MoE) are progressive and far-reaching, emphasising the importance of holistic, play-based early education. However, the learning outcomes of children continue to be low.

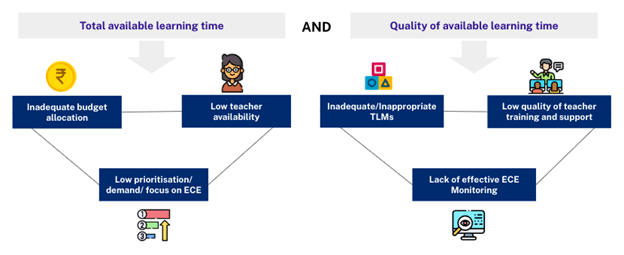

Systemic constraints to delivering quality ECE include low priority to ECE by both Ministries, significantly lower budgets for ECE in comparison to primary school years (~9x), and low availability of dedicated, qualified ECE teachers. There exists a need for research factors that may be strengthened to ensure quality ECE, such as teaching-learning time, teacher training, monitoring quality, parental perception of quality ECE and student learning outcomes.

Central Square Foundation undertook a situational analysis of ECE provisioning to understand the challenges and opportunities that can provide options to enhance ECE for young learners. Full report can be accessed here.

Study design:

This study involved conducting comprehensive desk research, followed by empirical research across seven states of India. The study employed a mixed-methods approach. The empirical analysis included an in-depth curriculum analysis, primary classroom observations and interviews with key stakeholders to comprehensively understand the country’s current public ECE provision models. The primary research was done in 13 districts across 7 Indian states, including observations in 200 ECE classrooms and interviews with 192 teachers, 140 parents, and 48 monitoring officials across both Anganwadis and Pre-Primary Sections in Government schools.

Gaps in service delivery have led to low effective learning time in ECE classrooms, which is a result of two factors: available learning time and effectiveness of learning. In this article, we focus on the insights from classroom observations and interviews.

Observations highlight that classrooms have learning-enabling resource provisions and environments. However, activity time and student engagement are low, impacting the overall quality of the limited learning time available within these classrooms.

Insights from classroom observations and interviews:

- Time spent on ECE activities in the classroom was low. No ECE activity took place in 25% of the classrooms that were observed. In classrooms where an ECE activity did take place, it was found that these activities accounted for only an average of 35 minutes out of a two-hour observation period. The average time spent on each activity was 13 minutes.

- The effectiveness of learning time was also poor. Within this limited time, the activities conducted were largely teacher-led, incorporating little time for hands-on activities and practice by children: Only 14% of the observed ECE activities followed the recommended approach of carrying out age-appropriate, student-led, small-group interactions. Additionally, the presence of activities involving play materials was limited. In cases where these activities were conducted, they were primarily led by the teacher, leaving little time for students to engage in independent exploration and practice. The most common activities that took place were alphabet, number, and poem recital.

For example, our data showed many instances of observations like this: “There were 30 students in the class. All the students come from three different Anganwadis. Some students were seen engaged in their own activity while most of the students were following and repeating the poem after the teacher.”

This may be because of the focus on ECE-related training. For instance, one of the teachers interviewed highlighted that this was a part of the training. “We learnt about poem/story recitation, numbers, student management, inculcating activities and discipline. The main focus was on poems and recitation”, she shared.

- Majority of teachers across all provision types (61%) did not ask questions to assess student understanding when introducing new concepts. When questions were asked, students’ responses were in a chorus format (83%). Insufficiently allocating time for activities impeded effective learning, as the gradual release of the responsibility model (I Do, We Do, You Do) was not properly implemented. This was further supported by the limited use of play materials and workbooks, limiting student practice opportunities.

An observer noted: “The activity was conducted in a way in which every student got the chance to participate. However, it seemed that the purpose of the activity was not fulfilled as the colour identification was not at all seen as the final outcome of the activity. Similarly, at the same time, a few kids were just putting the rings in the bottle without understanding the purpose of the activity, and the teacher did not guide them.”

In another activity, an observer noted: “Students followed the teacher and tried to imitate exactly what she did. There were around 12 students in the class during the activity, and all of them participated in it. Students were repeating the answers of body parts in chorus after the teacher said the names.”

This highlighted the need for better teacher preparedness and readiness to implement the curriculum. While 66% of the teachers had knowledge of the monthly plan in their curriculums, only 50% of the teachers could show the lesson plan for the day of the observation. This may indicate a lack of clarity of curriculum progression, leading to low usage and fidelity to lesson plans. This lack of preparedness resulted in teachers resorting to conducting simple, less engaging activities that did not seem to promote learning. This may lead to teachers usually preferring drawing and colouring, physical development activities and poem recitals.

For instance, one of the observers highlighted: “In this activity, the teacher started singing a poem and asked the student to follow her. She also made students do the actions along with singing to make them understand numeracy as well. After that, she immediately asked students to stand individually and recite one poem/number. For this, she picked only selected students who she felt could speak well”.

Interactions with parents and monitoring stakeholders highlighted that there was a low demand for quality ECE.

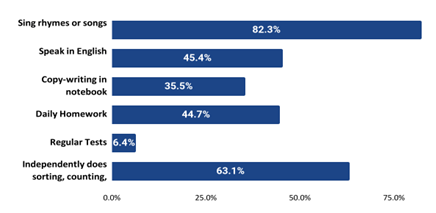

- Parents showed an active interest in their child’s learning but were unaware of how to best support them. Although there is an active interest in children’s learning, there is limited knowledge of what constitutes good ECE learning, school readiness, what to expect from an ECE teacher, and how to best support the child’s at-home learning. Parents defined quality early learning as their children’s ability to sing rhymes and speak in English.

- Interaction with officials indicated that there were competing priorities for their focus and implementation, highlighting a need for strengthening monitoring protocols for ECE programmes. A limited number of officials reported observing teachers engaging in ECE activities and actively monitoring student engagement, as well as offering constructive feedback as part of their roles and responsibilities. This highlights the potential for enhanced prioritisation and engagement in ECE-specific feedback and mentoring initiatives. One of the officials we spoke to highlighted: “We observe the Anganwadi. Do they check the child’s weight, or do the beneficiaries get the allotted benefits like food and health facilities? If they maintain a record of the same, if they have the Poshan tracker, how do they do it?”

Way forward for ECE in India:

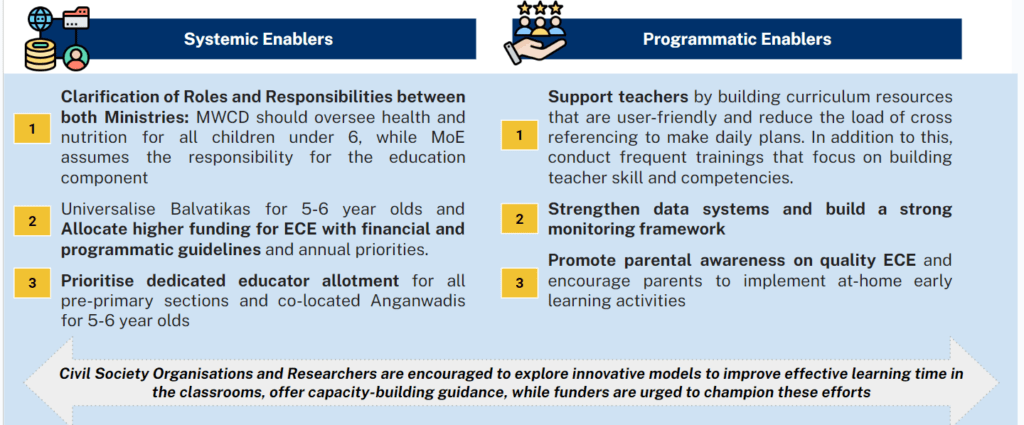

ECE policies in India are well-crafted and forward-looking. However, their implementation faces systemic challenges and operational hurdles. This has resulted in sub-optimal student learning outcomes and a conspicuous lack of school readiness. Elevating the status of early childhood education and bolstering its financial resources is imperative. Improved implementation of ECE policies will help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as goals set forth by the NIPUN Bharat Mission, ensuring enhanced learning for all children.

Central and state governments are crucial in creating an environment conducive to addressing these challenges. Donors and civil society organisations must focus on enhancing the evidence base on ‘what works’. Specific actions include:

Keywords

Authored by

Aditi Nangia

Senior Project Lead, CSF

Ashna Shah

Project Manager, CSF

CSF Editorial Team

Share this on