Go Back

Go BackShare

Cross-learnings from ‘health for all’ to achieve ‘learning for all’

By Manju Rani

Sep 29, 2021

Education and health are central to developing human capital and driving economic growth. Since independence, the Indian government has invested in building public health facilities (more than 200,000) and public schools (more than 1.5 million). However, despite free government healthcare facilities and schools, more than 50% households usually seek care from a private facility when sick and almost 40% primary school-age children attend private schools.

Education and health are central to developing human capital and driving economic growth. Since independence, the Indian government has invested in building public health facilities (more than 200,000) and public schools (more than 1.5 million). However, despite free government healthcare facilities and schools, more than 50% households usually seek care from a private facility when sick[1] and almost 40% primary school-age children attend private schools[2]. The population segmentation across government (mainly poor people) and private (for the better-to-do population) health facilities and schools is a matter of concern and has substantial implications for quality and equity[3].

While both health and education sectors face similar challenges (governance and accountability, human resource issues, poor perceived quality of services, inequities), the following sections highlight three potential cross-learning opportunities from the health sector to improve learning outcomes in the education sector.

The population segmentation across government (mainly poor people) and private (for the better-to-do population) health facilities and schools is a matter of concern and has substantial implications for quality and equity.

1. Community participation and mobilization: community-based health workers (ASHAs) and community-based education workers

Public health programmes have a long history of using community-based health care workers. India has nearly one-million women who are Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). They are present in almost every village across the country. They serve as an intermediary between the community and formal health care system.

ASHAs provide community outreach services which include health education, supporting mothers to access institutional delivery care, ensuring continuation of treatment of chronic diseases such as tuberculosis, and even screening for some of the chronic illnesses.

Community outreach and participation has also been attempted to some extent in the education sector — school staff members are part of campaigns run every academic year to identify out-of-school children and parental involvement is encouraged in school management committees or village education committees. But the effectiveness of such participation has been limited and the notion of teaching-learning has remained confined to a ‘school setting’ only. With the exception of Anganwadi workers for preschool education (there too, the primary focus is on nutrition), the concept of community-based education workers or community-based learning guides is yet to be fully leveraged in the education sector.

An evaluation of several participatory approaches found some positive impact of village youth volunteers organizing reading camps (Banerjee et al., 2010). Similar to ASHA workers in the health sector, more thought may be given on creating and supporting a network of community-based education workers who can provide child-centric support outside the formal school system and serve as an interface with formal schools. This is especially critical as governments try to build back better after the prolonged school closures due to the pandemic. Education workers can supplement formal instruction to reduce learning losses, especially in elementary grades.

Similar to ASHA workers in the health sector, more thought may be given on creating and supporting a network of community-based education workers who can provide child-centric support outside the formal school system and serve as an interface with formal schools.

2. Monitoring performance: Focus on outcome indicators and Institutionalization of household surveys to independently track them

The National Health Policy (2017)[4] clearly specified a set of outcome indicators with a time-bound target (e.g. reduce under-5 mortality to 23 by 2025 or reduce infant mortality to 28 by 2019, etc.), the same may be specified in education policies through an accompanying monitoring and evaluation framework. For instance, the National Education Policy 2020 specifies a target of universal acquisition of foundational literacy and numeracy skills at primary level by 2026-27. SDG 4.1.1 too specifies that children must achieve at least a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics. However, we need more specific and defined targets to ensure improved learning outcomes and also a reliable system to track progress against these targets.

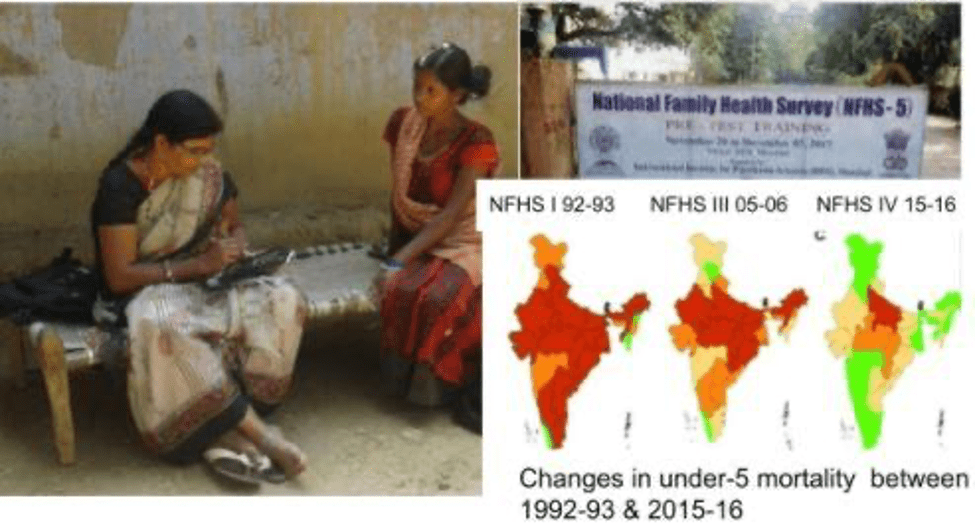

Regular administrative data collected from health facilities and schools suffer from incompleteness, delays, inaccuracies, etc., and may not be suitable for outcome tracking at population level. In health, in addition to the administrative data, periodic representative household surveys such as the National and Family and Health Surveys (NFHS) and National Sample Surveys (NSS) have become an integral part of the ‘National Health Information’ systems which measure and monitor key outcome indicators such as infant- or under-5- mortality rate as well as output- or coverage- indicators such as immunization coverage or institutional delivery rates. The surveys also help to validate the administrative data on coverage and outcomes to improve its quality. In 2019-20, the Ministry of Health conducted the fifth round of NFHS; the first round was conducted in 1992. NFHS provides invaluable data to monitor trends in key outcome and coverage indicators over the past 3 decades.

Much like institutionalization of different household surveys in the health sector to track key outcome indicators in addition to administrative data from health facilities, the education sector can also include periodic household surveys that measure learning outcomes as an integral part of the national educational information system to independently track learning levels for each and every child.

Household surveys to measure educational outcomes is relatively a new concept. Though some of the household health surveys (e.g., NFHS, education module of NSSO) collect data on enrolment and school completion rates, the assessment of learning outcomes relies mainly on in-school assessment. The National Achievement Survey (NAS) is the only government-led school-based survey that assesses learning levels. NAS was instituted in 2011-2 and is conducted by NCERT every three years with the most recent one in 2017-18[5]. While great to get a snapshot of the health of the school education system, in the past it has missed out on out-of-school children, and children studying in private schools. It may also have inherent conflict of interest issues with potential inflation of the learning levels (Johnson and Parrado, 2021). The Ministry of Education’s decision to include children studying in private unaided recognized schools in NAS 2021 will help address some of the issues raised above.

The Annual State of Education Report (ASER) by Pratham, a non-profit organisation in the education sector, is an example of a household survey that demonstrated how learning outcomes can be successfully tracked and measured for meaningful interventions at the systemic level.

Much like institutionalization of different household surveys in the health sector to track key outcome indicators in addition to administrative data from health facilities, the education sector can also include periodic household surveys that measure learning outcomes as an integral part of the national educational information system to independently track learning levels for each and every child.

3. Unique patient ID and patient record and unique student ID and student record:

In 2020, the government launched the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM)[6][7] to create unique Health IDs, longitudinal electronic health records, and health provider and health facility registries which may all have substantial impact on the quality and continuity of healthcare facilities. Though the NDHM is still a work in progress, a similar National Digital Education Mission in the education sector with unique student ID and longitudinal student record can be transformational. Unified District information system (UDISE) launched in 1994 is already a step in that direction and has already substantially improved the availability of educational statistics.

Unique student IDs in education will allow the learning journey’s of all children to be captured and measured. This can include school enrollment, government schemes they might have adopted, and learning levels. If executed well, such a database will lead to more accurate estimation of enrollment, drop-out rates, and will do away with the system of transfer certificate (TC) facilitating seamless transition of students from one school to another. It is being introduced for some years in Australia.[8]

Unique student IDs in education will allow the learning journey’s of all children to be captured and measured. This can include school enrollment, government schemes they might have adopted, and learning levels.

Education can learn from health

To summarize, the education and health sector face similar challenges ranging from human resources (absenteeism, quality), inputs, and access versus quality. However, education delivery can definitely be strengthened based on learnings from the healthcare sector: community involvement, establishing clear outcome-oriented targets which are also regularly monitored, and unique education IDs for all students.

View Article References

Keywords

Authored by

Manju Rani

Founding member, SMILE

Share this on